You Cannot Click This Link

Foreign influence in our media is a problem, but what about our own influence over the platforms that govern what we see?

Foreign interference in U.S. politics is not a distant memory from 2016. It’s an ongoing, evolving threat that has become multi-dimensional and much more widespread. For the moment, let’s focus on the recent Iranian hack of the Trump campaign and set aside the indictment of NYC Mayor Eric Adams, the recent Microsoft cyber threat report on Russian disinformation, the new accusations of Chinese fake news sites, the Iranian intelligence plot to assassinate Donald Trump, and…well, you get the point.

The Trump campaign hack is a problem on its own. A major focus of this newsletter is to discuss the question of what information we are consuming and who is producing it, and the hack is an obvious installment of that discussion. It also showcases another problem deserving of our attention: the influence, power, and censorship abilities of those who own our digital platforms.

Iranian Hack of the Trump Campaign

The U.S. Department of Justice claimed last month that Iranian hackers were responsible for attempted hacks of the Trump campaign, the Harris campaign, and several CIA agents. The DoJ made it clear that they were successful in gaining access to private Trump campaign documents, which Iran then sent to major U.S. media outlets to be published. Those outlets refused to publish the information, which is an interesting wrinkle we will discuss shortly.

We now have more information about the hacks after the DoJ unsealed an indictment against three Iranian men they claim are responsible. For the successful Trump campaign hack, the DoJ alleges the Iranians set up a fake email account four years ago impersonating Ginni Thomas, the wife of Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas. They spent those four years building a digital trail to provide the account some legitimacy, then using it to send phishing links to senior campaign officials. They gained access to Roger Stone’s email account, which they used to steal private documents from the campaign. Be careful what you click on, folks.

As was the case with the Hunter Biden laptop information, the hackers sent their stolen documents to major media outlets for publication to harm their targeted candidate – Trump, in this case. Those outlets, following the precedent they set during the Hunter Biden incident, refused to publish the information, claiming that its publication would only encourage future hackers if they knew they could easily get their dirt into U.S. news cycles. Some cried foul, still upset about the 2016 Russian hacks of John Podesta and the voracious media coverage those documents earned through election day. Ultimately, however, this is probably the right stance, for the same reasons why buying stolen goods is illegal–you create an incentive for more theft if there’s an easily accessible market for what you have stolen.

That said, it does feel paternalistic for major media outlet heads to decide unilaterally what the public sees. At a time when trust in media is at rock bottom, depriving viewers of seeing those documents doesn’t help. This issue was made all the more interesting when independent journalist Ken Klippenstein published the documents anyway. The documents turned out to be the Trump campaign’s oppo research file on JD Vance and were frankly an objectively mundane and anticlimactic read.

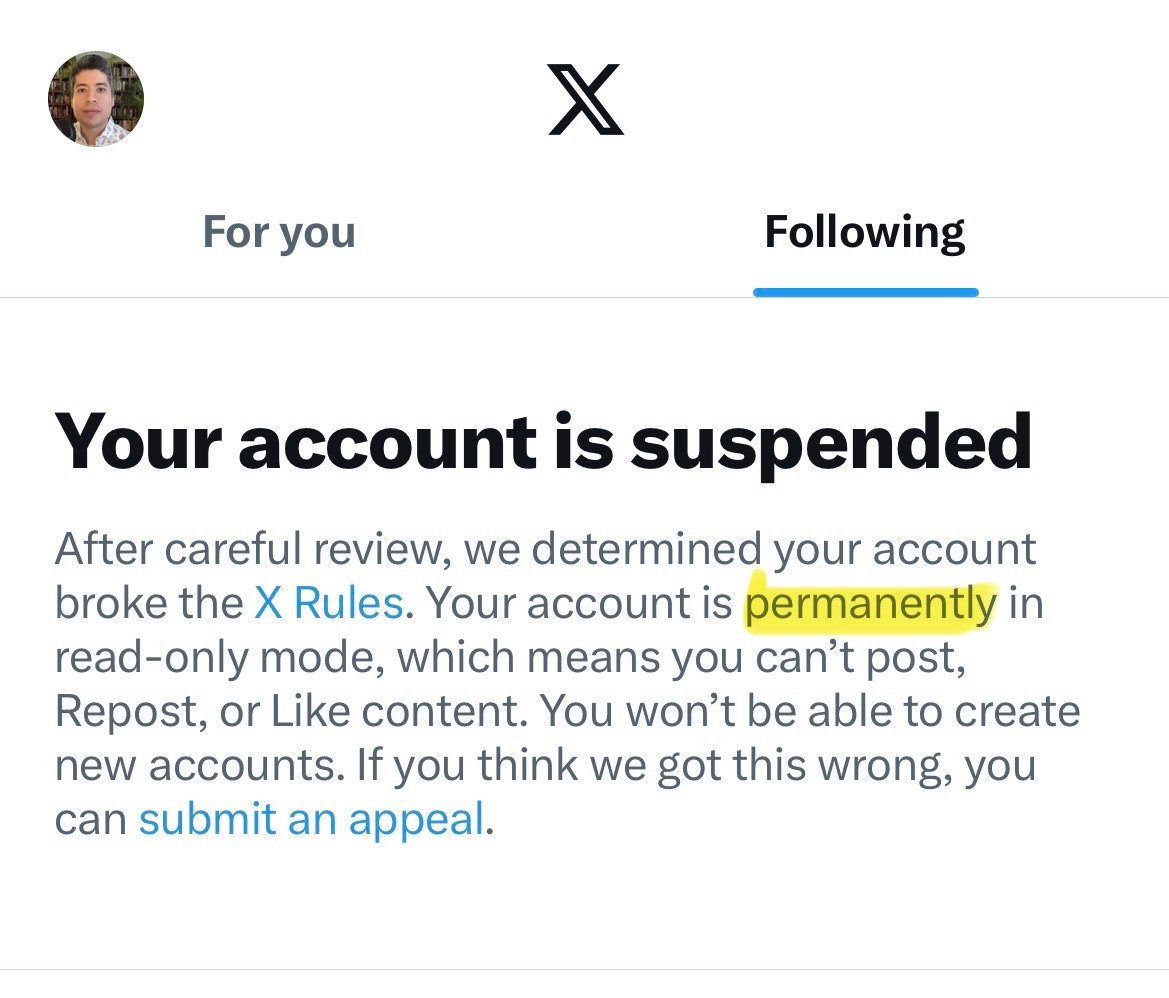

What then happened to Klippenstein is far more interesting. Minutes after posting the documents on Twitter/X, his account was permanently banned for “posting private information,” which Elon Musk says is because the documents contained JD Vance’s home address and part of his social security number. Klippenstein has since redacted that information, but his ban remains in effect, and accuses Musk, a vocal Trump supporter of banning him for political purposes. He fairly points out that no user was banned for posting much more salacious private information about Hunter Biden and we have discussed in previous newsletters, Musk’s content moderation policy is incoherent at best.

While the documents are still up on Klippenstein’s substack, other media platforms have outright banned any link that brings you to the information. As of today, you cannot post a direct link to the document on X, while Meta has taken action to prevent its spread on Facebook and Instagram. Most shockingly, Google has blocked users from importing the document to Google Drive or sharing it with others on that platform.

It’s Not Just the Noise

This is a stark reminder that the noisy information we are bombarded with is only part of the problem. At the end of the day, that information lives on digital platforms governed by a small subset of powerful people. At worst, they are partisan hacks operating in bad faith, as Musk likely is. At best, they are the heads of trillion-dollar for-profit enterprises who weigh a litany of conflicting interests, none of which, I suspect, are an altruistic appreciation for the difficult balance of user safety and agency. Call me a cynic, if you must.

I initially assumed Meta and Google blocked access to the document for cybersecurity reasons; the document, after all, came from an Iranian hacker who had just phished the Trump campaign using malicious links. I was proven wrong when Google stated they were restricting access to the document due to a violation of their “personal and confidential information policy.” Even if you buy that argument, Meta was much more clear that their restriction was about combating foreign influence in our politics and media.

My cynicism about these companies’ actions may seem odd considering how intense a threat I consider foreign influence is on our media. In fact, I disagree with Klippenstein’s argument that foreign interference isn’t a sufficient reason to censor information online. Ultimately, however, these are the very companies that are failing to address countless other instances of pure and malicious misinformation posted by hostile foreign nations. The Trump campaign document may have been the product of an Iranian hack, but at the end of the day, it’s a real document with real information. They have limited the public’s access to it while Russian-made deep fake videos continue to flow, even if the platforms are “doing their best” to take them down.

I won’t pretend this is a black-and-white ethical decision. There’s a lot to consider here and if we assume these are good-faith arguments, I get why they did what they did. But this is a stark reminder that we don’t just have a noise problem online. Our digital platforms are governed by fallible and imperfect people who decide what we see and when we see it. The information we consume is not shown to us through some democratic process or virality-based meritocracy; it is uplifted by a man-made algorithm that we cannot access and is subject to censorship at the whims of unelected elites. Our information ecosystem is not some Hobbesian state of nature, it is under our control and we are doing a very bad job at controlling it.